Tags

Climate Change Denial, Climate Tipping Points, Collapse of Civilizations, Degrowth, Ecological Overshoot, Energy Transition, Fossil Fuel Dependency, Green Revolution, Haber–Bosch Process, Hubris of Man, Planetary Boundaries, Systemic Collapse, The Anthropocene Age, Weapons of Mass Destruction

Introduction: The Paradox of Progress

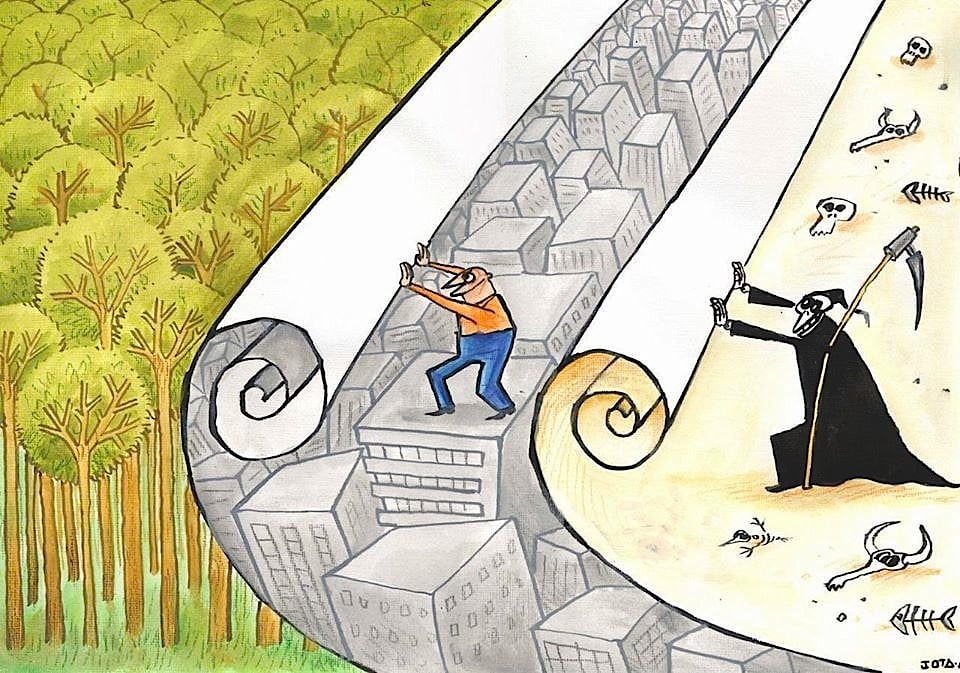

Humanity’s ascent from a marginal species to a planetary force is a tale of ingenuity, ambition, and unintended consequences. Over millennia, four foundational innovations—the control of fire, the Agricultural Revolution, the Haber-Bosch process, and fossil fuels—enabled humans to overcome biological and ecological constraints, catalyzing explosive population growth. Yet these same advancements have propelled us into ecological overshoot, a state where our demands on Earth’s systems outstrip its capacity to regenerate. By the 1970s, humanity crossed this critical threshold, entering an era of debt-driven consumption fueled by finite resources. Compounding this crisis are weapons of mass destruction (WMDs)—technologies of annihilation with no purpose but destruction—and the deliberate suppression of climate science by fossil fuel corporations, which prioritized profit over planetary habitability.

As we approach 2050, the consequences of this trajectory loom: destabilized ecosystems, collapsing biodiversity, and a climate system veering toward irreversible tipping points. Yet even as renewable energy expands, systemic barriers—transmission bottlenecks, industrial inertia, and geopolitical fractures—paint a sobering picture of the future. A 2025 J.P. Morgan report, Heliocentrism: Objects may be further away than they appear, underscores that the energy transition remains linear, not exponential, with renewables accounting for just ~2% of global final energy consumption. This reality forces a reckoning: the path to sustainability will be neither swift nor absolute. The same species that mastered fire and split the atom now faces a choice—adapt or perish.

1. Control of Fire: The First Spark of Dominance

The mastery of fire, achieved by early hominids like Homo erectus roughly 1.5 million years ago, marked humanity’s first departure from the natural order. Fire provided warmth, protection from predators, and the ability to cook food, which unlocked greater caloric intake and spurred brain expansion. Archaeological evidence, such as charred bones and hearths in Kenya’s Koobi Fora region, suggests controlled fire use became widespread by 400,000 BCE. Fire also became a tool for landscape engineering. Indigenous societies used controlled burns to flush out game, clear land for foraging, and cultivate fire-resistant plants. In Australia, Aboriginal fire-stick farming shaped ecosystems for millennia, creating savannas that supported human communities but reduced biodiversity.

This early manipulation of ecosystems set a precedent: humans could reshape environments to suit their needs, a power that would escalate dramatically. By improving survival rates and enabling migration into colder climates, fire supported gradual population growth. However, its impact was localized—a far cry from the global transformations to come.

2. The Agricultural Revolution: Taming Nature, Unleashing Growth

Around 10,000 BCE, in the Fertile Crescent, the Neolithic Revolution began. Humans domesticated wheat, barley, and legumes, while in Mesoamerica, maize emerged as a staple. Simultaneously, animals like goats, sheep, and cattle were tamed, providing meat, milk, and labor. This shift from nomadic foraging to settled farming was not inevitable; climate stability after the last Ice Age likely played a role. Agriculture generated food surpluses, enabling population densification and labor specialization. Pottery, metallurgy, and writing emerged, as did social hierarchies—rulers, priests, and warriors. Cities like Uruk in Mesopotamia and Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley thrived, housing tens of thousands by 3000 BCE.

Farming demanded deforestation, irrigation, and monocultures. In Sumer, excessive irrigation led to soil salinization, collapsing yields by 2000 BCE. Similarly, Easter Island’s deforestation for agriculture triggered societal collapse by 1600 CE. Yet Earth’s carrying capacity seemed vast enough to absorb these early failures. Global population surged from ~5 million in 10,000 BCE to ~300 million by 1 CE. Agriculture’s success, however, hinged on exploiting new lands—a strategy with finite limits.

Today, industrial agriculture faces a parallel crisis. Synthetic fertilizers and fossil-fueled machinery have boosted yields but degraded 40% of global soils. The J.P. Morgan report warns that topsoil erosion now outpaces replenishment by 10–40 times, threatening 90% of soils by 2050. Regenerative practices remain niche, hampered by short-term profit motives and entrenched supply chains.

3. The Haber-Bosch Process: Cheating the Nitrogen Cycle

By the late 19th century, population growth strained agricultural systems. Natural fertilizers—guano from Peru, manure from livestock—were insufficient. Scientists warned of mass starvation as nitrogen, critical for plant growth, became scarce. In 1909, German chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch industrialized ammonia synthesis, reacting atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) with hydrogen (H₂) under high heat and pressure. The Haber-Bosch process effectively “fixed” nitrogen from the air, creating synthetic fertilizers. By 1940, global ammonia production reached 4 million tons annually.

Post-World War II, synthetic fertilizers became the backbone of the Green Revolution. High-yield crop varieties, like Norman Borlaug’s dwarf wheat, depended on nitrogen inputs. From 1950 to 2000, global grain production tripled, supporting a population boom from 2.5 billion to 6 billion. Today, half the nitrogen in human tissues originates from Haber-Bosch. The process tethered agriculture to fossil fuels (hydrogen is derived from methane) and flooded ecosystems with excess nitrogen. Runoff into waterways causes algal blooms and dead zones, like the 6,500-square-mile zone in the Gulf of Mexico. Nitrous oxide (N₂O), a byproduct of fertilizer use, is a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than CO₂.

The J.P. Morgan report highlights a stark trade-off: without Haber-Bosch, Earth’s carrying capacity would plummet to ~3–4 billion. Yet decarbonizing fertilizer production remains a distant goal. Green hydrogen, produced via renewable-powered electrolysis, costs 4–5x more than methane-derived hydrogen, and scaling it would require unprecedented investment in wind, solar, and grid infrastructure.

4. Fossil Fuels: The Engine of Overshoot

The 18th-century harnessing of coal unlocked unprecedented energy density. James Watt’s steam engine (1776) powered factories, railroads, and ships, enabling mass production and global trade. By 1900, coal supplied 90% of the world’s energy. The 20th century belonged to oil. The internal combustion engine revolutionized transportation, while petrochemicals spawned plastics, pesticides, and synthetics. From 1950 to 2000, oil consumption grew sixfold, fueling suburbanization, globalization, and consumer culture.

Fossil fuels powered the pumps, tractors, and fertilizer plants of industrial agriculture. Between 1960 and 2000, irrigated land doubled, much of it relying on diesel pumps draining ancient aquifers. In 1971, humanity’s resource demand first exceeded Earth’s annual regenerative capacity, according to the Global Footprint Network. This “overshoot day” has crept earlier yearly, landing on July 28 in 2023. Of particular interest is this day’s arrival if the world consumed like citizens of any particular country. For Qatar, that day would fall on February 6; for the United States, March 13; for China, May 17.

Fossil fuels enabled this rupture by accelerating resource extraction, driving climate change, and entrenching inequality.

The J.P. Morgan report underscores fossil fuels’ enduring role. Despite record solar installations, renewables account for just 7% of global electricity generation. Natural gas, touted as a “bridge fuel,” will remain critical for grid stability and industrial processes. Global LNG export capacity is set to grow 33% by 2030, with Europe increasingly reliant on gas to offset coal phaseouts.

5. Weapons of Mass Destruction: The Ultimate Unsustainability

The 1945 Trinity test marked humanity’s entry into the Anthropocene. Nuclear arsenals grew to over 70,000 warheads during the Cold War, enough to destroy civilization multiple times over. Though stockpiles have decreased to ~12,119 today, modernization programs in the U.S., Russia, and China keep the threat alive. Nuclear testing alone has left lasting scars: the Marshall Islands remain uninhabitable after 67 U.S. tests, while Semipalatinsk in Kazakhstan reports elevated cancer rates from Soviet explosions.

The production of WMDs diverts resources—$91.4 billion spent globally on nuclear arms in 2024 could fund renewable transitions. WMDs exemplify humanity’s disconnect from ecological stewardship. Unlike earlier tools for survival, they serve no purpose but annihilation, reflecting a mindset that prioritizes dominance over coexistence.

6. Suppressed Science: The Fossil Fuel Industry’s Betrayal

Internal documents reveal that Exxon scientists, in the 1970s, accurately predicted the trajectory of CO₂-driven global warming. A 1982 memo stated fossil fuel use would cause “potentially catastrophic events” by 2050. Instead of acting, Exxon, Shell, and Chevron funded groups like the Global Climate Coalition to sow doubt. From 1989 to 2015, the Koch Brothers funneled $145 million to climate denial groups. This playbook mirrored Big Tobacco’s tactics, delaying regulatory action for decades.

Had global CO₂ emissions peaked around 2000, it might have been possible to limit warming to 1.5°C. Instead, emissions have continued to rise, reaching record levels in 2024. The J.P. Morgan report notes that methane leaks from U.S. gas basins, detected via satellite, are 4–5x higher than industry reports—a stark reminder of systemic opacity.

Ecological Overshoot: Symptoms of a Planet in Distress

The Earth is hemorrhaging life. Vertebrate populations—mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles—have plummeted by 73% since 1970, a collapse that mirrors the unraveling of ecosystems worldwide. This staggering loss, documented by the World Wildlife Fund (2024), is compounded by an “insect apocalypse,” with pollinator species vanishing at 1–2% annually. These creatures, vital to food systems and biodiversity, are succumbing to habitat destruction, pesticides, and climate disruption.

Even the planet’s lungs are failing. The Amazon rainforest, once a carbon sink absorbing 5% of global CO₂ emissions, now emits more greenhouse gases than it captures due to rampant deforestation and wildfires. Meanwhile, Arctic permafrost—thawing decades ahead of scientific projections—risks unleashing 1,400 gigatons of methane, a greenhouse gas 80 times more potent than CO₂ over 20 years.

Humanity’s exploitation of finite resources has pushed Earth’s systems to the brink. Freshwater withdrawals in critical regions like the North China Plain exceed recharge rates by 300%, draining aquifers that sustain millions. Industrial agriculture, reliant on synthetic fertilizers, has poisoned waterways with nitrogen runoff, creating dead zones like the 6,500-square-mile graveyard in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Road to 2050: Scenarios for Humanity

If emissions continue, warming could reach 2.4–2.7°C by 2050, triggering cascading crop failures, mass migration of 216 million, and uninhabitable zones in the Gulf Coast and South Asia. Aggressive renewable transitions might limit warming to 2°C, but legacy damage—acidified oceans, depleted soils—would still cause widespread famine and conflict.

The J.P. Morgan report Heliocentrism: 15th Annual Energy Paper (2025) casts significant doubt on the feasibility of a full global transition to 100% renewable energy by mid-century, citing systemic, economic, and technological barriers. While solar and wind capacity are expanding rapidly, the report emphasizes that the energy transition remains linear, not exponential, and faces critical limitations:

The “Final Energy” Challenge

Renewables account for just ~2% of global final energy consumption (not just electricity), projected to rise to 4.5% by 2027. Electricity itself represents only ~20% of global energy use, with fossil fuels still dominant in transportation, industrial heat, and manufacturing. Even if solar generation doubles by 2027, it would supply less than 5% of total energy needs. Industrial sectors like steel, cement, and chemicals rely on fossil fuels for 80–85% of their energy, and electrifying these processes remains prohibitively expensive without breakthroughs.

Grid Limitations and Infrastructure Gaps

-

Transmission Bottlenecks: U.S. transmission line growth lags far behind Department of Energy targets, with annual additions at ~1,000 miles vs. the 6,000–10,000 miles needed by 2035.

-

Transformer Shortages: Delivery times for transformers have ballooned from 4–6 weeks in 2019 to 2–3 years due to supply chain constraints and aging infrastructure.

-

Intermittency: Even in renewable leaders like California, wind and solar + storage meet 75%+ of demand in only 26% of annual hours. Baseload fossil fuel or nuclear power remains essential for reliability.

Economic and Geopolitical Risks

-

China’s Solar Dominance: China controls 80% of solar manufacturing (polysilicon, wafers, cells), creating supply chain vulnerabilities. U.S. tariffs and efforts to build domestic capacity are progressing slowly.

-

Cost Inflation: Rising U.S. solar PPA prices (due to tariffs, insurance premiums, and interest rates) and Europe’s energy price spikes (5–7x higher than China/India) threaten affordability.

Industrial and Thermodynamic Realities

-

Steel, Cement, and Aviation: These sectors lack scalable green alternatives. Renewable jet fuel costs 4–6x more than conventional fuel, and synthetic fuels face energy deficits (e.g., producing synthetic methane requires 3x more energy input than output).

-

Hydrogen Hurdles: Green hydrogen remains uneconomical (85–165/ton CO₂ abatement costs) due to electrolyzer expenses, leakage risks, and energy losses in conversion.

The Fossil Fuel “Bridge”

The report argues that natural gas will remain critical for grid stability and industrial processes for decades. Global LNG export capacity is set to grow 33% by 2030, and regions like Europe increasingly rely on gas to offset coal phaseouts.

Nuclear’s Uncertain Role

While nuclear power offers zero-carbon baseload energy, the OECD has struggled to build new plants due to cost overruns, regulatory delays, and public opposition. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) remain unproven at scale, with projected costs of $15–20 million/MW—far above competitive thresholds.

Conclusion: A “Hybrid” Future, Not 100% Renewables

The report concludes that a 100% renewable global economy by 2050 is unrealistic without unprecedented breakthroughs in grid infrastructure, energy storage, and industrial decarbonization. Instead, it envisions a hybrid system:

-

Solar/wind dominance in electricity (50–70% by 2050), paired with gas/coal + carbon capture for backup.

-

Nuclear and geothermal filling gaps in baseload power.

-

Fossil fuels persisting in heavy industry and transportation until 2040–2050.

In short, the report underscores that the energy transition is a century-scale industrial shift, not a rapid revolution. Without radical policy interventions, global cooperation, and trillions in infrastructure investment, fossil fuels will remain entrenched—even as renewables expand.

A global “Marshall Plan” deploying degrowth economics and regenerative agriculture could stabilize populations. Yet this requires dismantling entrenched power structures—a prospect hindered by nationalism and corporate influence.

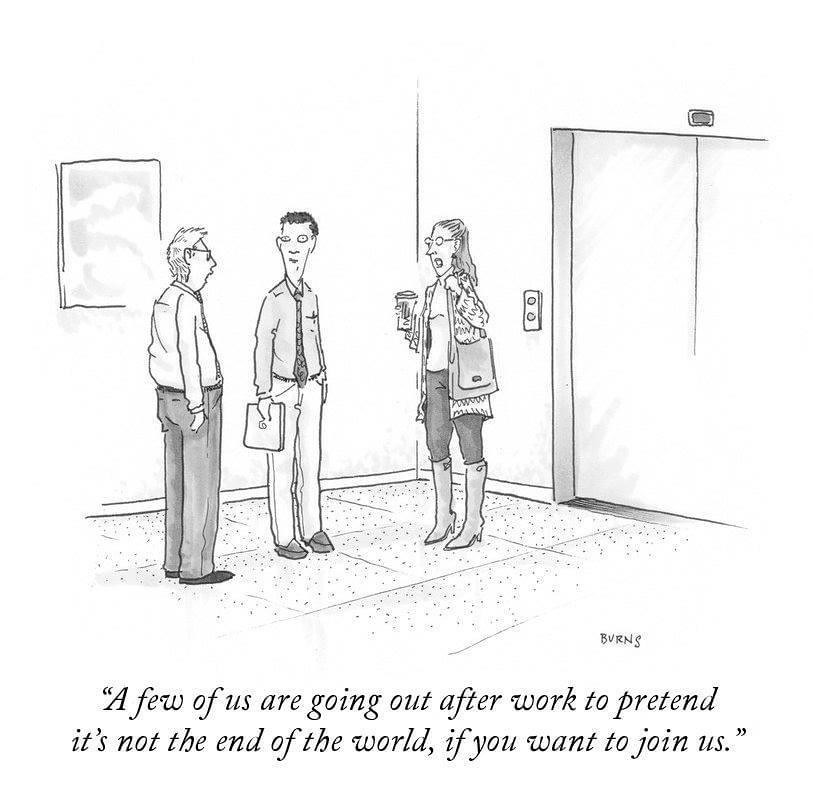

The more we accept the likelihood of collapse, the more urgently we must act as if it’s avoidable. To abandon agency is to accelerate the cancellation of the future; to cling to salvation myths is to blind ourselves to adaptation. The path forward is neither hope nor despair, but a third space: ethical endurance.